Not many people can say “been there, done that” on the metaverse. But Raph Koster, CEO of Playable Worlds, has been making online worlds for more than a quarter of a century.

He gave a speech about what he’s learned from that experience at our GamesBeat Summit: Into the Metaverse 2 online event today. Koster has worked on online game worlds such as Ultima Online, EverQuest, and Star Wars Galaxies, and he understands the difficulty of interoperability, how people behave, the importance of creating standards, and the need to focus on fun.

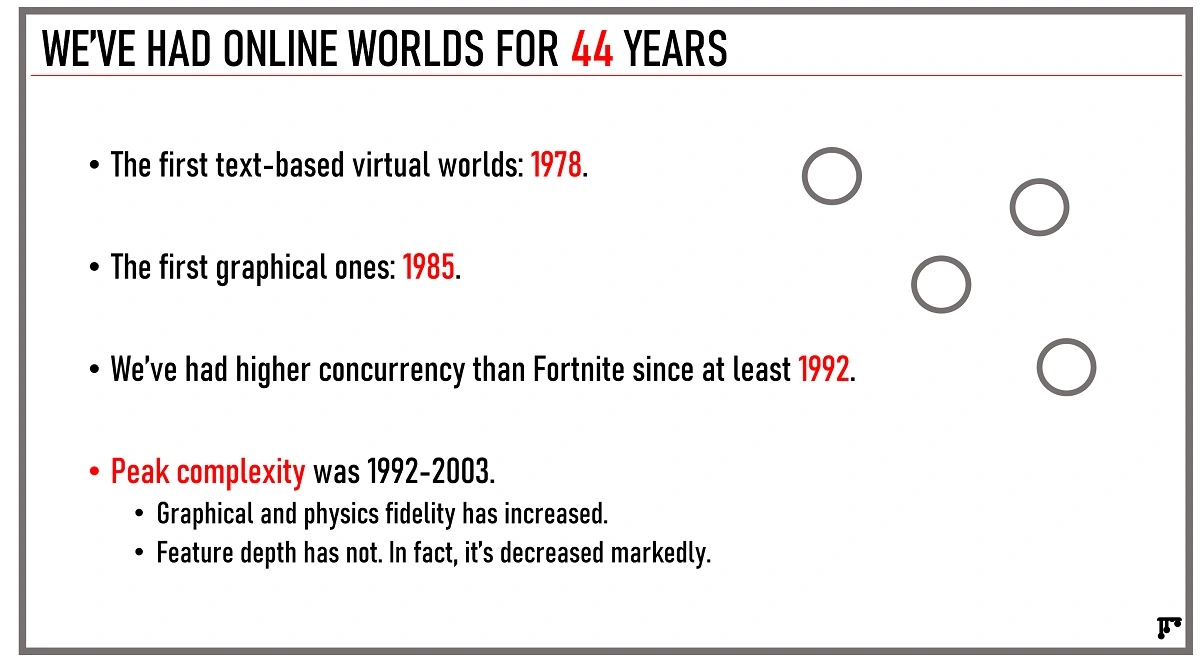

“I’m here to just share some high level lessons, some mistakes that have already been made, in hopes that it saves you from making future mistakes,” he said. “We’ve had online worlds for 44 years, and any vision of the metaverse is built on top of the idea of online worlds, whether you call them online worlds, MUDs (multi-user dungeons), virtual worlds social worlds — it doesn’t matter.”

He said we’ve had online worlds since 1978. We’ve had graphics in them since 1985. And we’ve been supporting thousands of players in a world since the late 90s, Koster said. And we have had hundreds of players in a single world since at least 1992. He said the peak of complexity in virtual worlds was between 1992 and 2003.

“A lot of the problems that people think are major core technology challenges to surmount, were actually handled a quite a long time ago,” he said. “Ever since we’ve been simplifying them in order to reach broader and broader markets. So it’s important to bear in mind that the potential that people want to explore has often been explored before. And there’s a lot of things that we could have as takeaways from that time period.”

Previous metaverses

He noted that the game industry has even built multiverses before.

“This is the idea of taking multiple online worlds and cross connecting them with basically hyperlink connections, and having them share enough of an engine framework that players can hop freely between them with one client,” Koster said. “Much like one browser allows you to hop between different web pages. But even to the degree where players can experience this content because the technology underneath allows content to be shared across the worlds.”

At the peak, these older worlds were decentralized worlds, run by volunteers and running on open source software.

“So many of the dreams that people have today for what a decentralized metaverse can look like, actually existed all the way back in 1992,” Koster said. “And it’s important to ask ourselves the question, why is it that that didn’t stick and didn’t take. And of course, to make something into a true metaverse, we need real world connectivity. The first time I personally built a virtual version of real world stores in a mall was in 1994.”

That’s how long the metaverses have had a connection to the real world. He said virtual concerts have had total bidirectional audience interaction for ages.

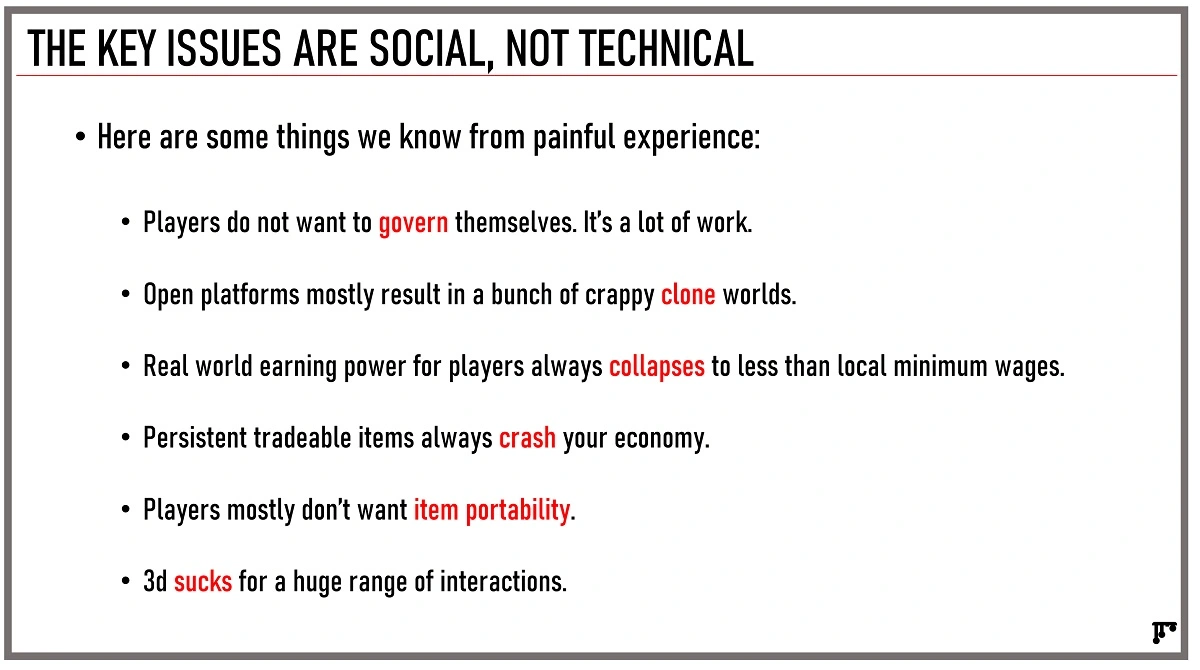

“The ability to carry avatar identity across different worlds ages, interactivity with classrooms, where users could complete assignments in a virtual world and have grades show up ages. None of these things are truly new,” he said. “And the big lesson here is that the big challenges to surmount are social not technical.”

Crappy UGC and mudflation ‘play-to-earn’

He said we still have major dreams, but we have failed to deliver so far in the history of online worlds and metaverses. Ongoing challenges include “crappy voluminous user-generated content,” he said.

He noted that “play-to-earn” games, where users can earn money or rewards playing, have always had the risk of “drifting down below livability thresholds, where the economy crashes due to what gets called “mudflation.”

Koster said that players have not been that interested in item portability, and the fact that 3D is not really a salve for a lot of the typical experiences the players want.

“Each of these should be regarded as a challenge, not as a permanent barrier. But to enter into this space without seeing these as major unsolved problems with decades of standing is to not really be aware of our own history,” Koster said.

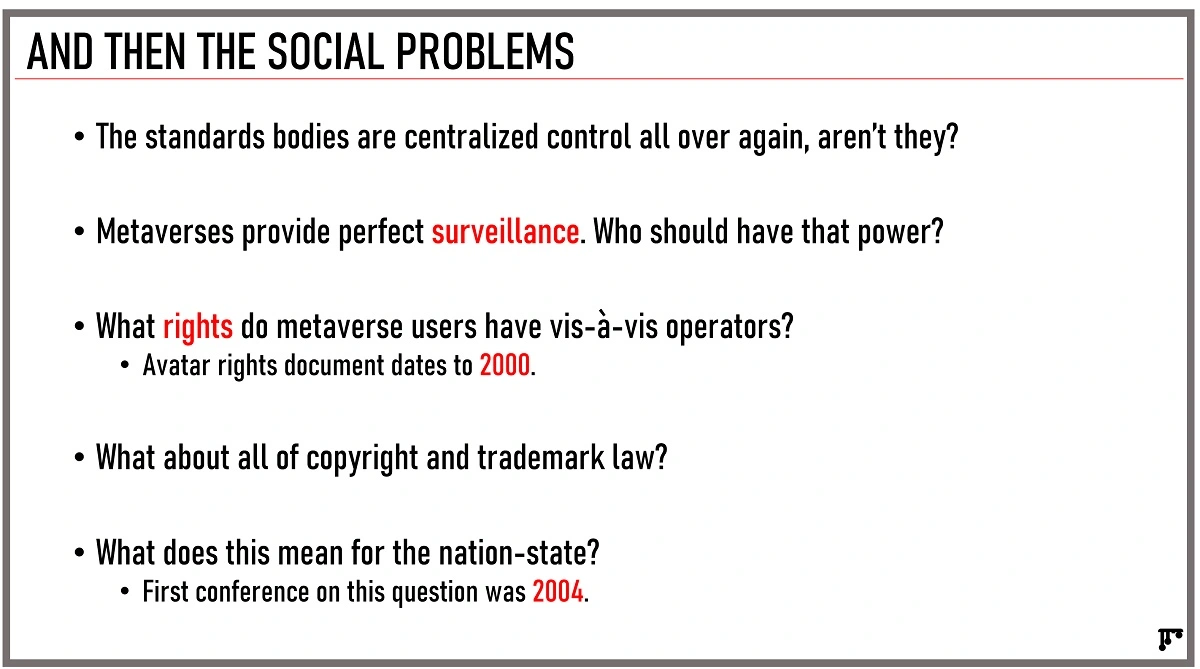

One example is this dream about data portability, or taking the things you buy in one game, like a sword or an avatar, to another. He said data portability can’t happen without standards, and standards are a social coordination problem.

“And worse, there is a social coordination problem that centralizes control,” he said. “If we dream of decentralizing things, we have to deal with the social challenges of getting potentially thousands of developers aligned to one direction. Bear in mind that right now, the two major game engines are Unity and Unreal, and they do not even agree whether the “y axis” means up. That is how far apart we are on basic standards.”

He said the open web is a model for the kind of standard for decentralized creativity, for commerce, and so on.

“We have spent the last 20 years undermining the original open web and the way it was designed everything from pushing more and more fancy rendering into the clients rather than driving it from the cloud,” he said.

That has centralized much of the business infrastructure in the name of making money.

“Those same challenges are going to exist for the metaverse. What is it going to take to really get there? Any real metaverse has to embrace the idea that any device should be able to be a client,” he said. “And that implies a whole bunch of open standards on the protocol, not narrowing down to just one engine being the back end and so on. It implies not focusing to the degree that we do on high-end rendering.”

Is 2D better?

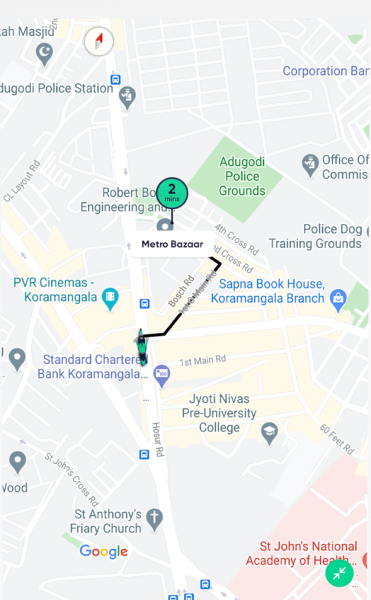

He said an enormous amount of the metaverse needs are going to be flat. He noted that 2D works for things like Yelp and Google Maps because some metaverse data will always work better in a 2D display than in a 3d display.

“And the classic example of virtual worlds have taught us is that having to wander a giant endless mall in 3D is a terrible experience,” he said. “Frankly, wandering giant, endless worlds of any sort has tended not to be a great experience for users. We’re going to have to relearn the lesson that we can’t ship content as beautiful, sculptural 3D assets. In particular, maps cannot be 3D sculpts.”

In a true metaverse, players might be interacting with World of Warcraft and with Google Maps simultaneously. He said we need to be able to treat environments as raw data.

“Someday, we may want to walk across a map that actually represents the movement of stocks on the stock market in real time,” he said. “If we are shipping big maps that are 3D sculpts, then they can’t change and unlock new kinds of behaviors on the fly. If we want to unlock the power of cloud simulation, we need to get away from thinking of environments as being static content.”

Similarly, he said the art we see needs to break away from the notion that it is something baked into a client. He said current engines still work very much like they were intended to with games shipped on disks. He said we bake all of the art into the client, and it takes hours to do a build.

“Try to picture patching your browser every time Amazon adds a book to their storefront,” he said. “That is the current state of the art for game engines. It is obvious that, as the metaverse develops, everything needs to be able to come down on the fly and be driven entirely from the cloud. And ideally, not from one central content repository. But just like images on the web, from arbitrary URLs all over the internet, because that is what would truly unlock user generated content.”

And if we want a decentralized metaverse — one that is open and not controlled by one party — we obviously need to decentralize control.

Godlike power

“As somebody who has operated online worlds for literally decades, I can tell you that the ethical questions that end up keeping me up at night are around the fact that I as a god of a world have godlike power,” he said. “I have the ability to surveil, I have the ability to data analyze, I have the ability to control what people see. Truly online worlds and by extension metaverses are a panopticon where I control the vertical and I control the horizontal.”

Exploring how we arrive at models of governance, how we arrive at ways for players to be expressive, and free in a metaverse is not a simple or easy problem, he said.

He said the industry has been wrestling with the challenges of governance ever since the infamous rape in cyberspace case around 1993. The technical infrastructure to enable this implies the ideal architecture is quite different from how things work today, even if we solve the substantial problem of having all the different clients able to use same 3D asset format, he said.

“That doesn’t mean that they come with functionality. The biggest barrier to item portability is actually that every single game and every world implements that functionality in completely different ways,” he said. “There are zero shared data structures across items between two different games, even two of them built on the same engine. And we know from the experience of open source virtual world platforms, that once they are released, they quickly begin to diverge in capability.”

So compatibility begins to erode over time. He said that one possibility is to take a cue from platforms like web-publishing tool WordPress, which allows a plugin architecture and shifts as much functionality as possible into soft code in order to allow different platforms to implement the same applications programming interface (API), he said.

“But just the coordination challenge of building that API is likely to be a multi-decade process of arriving at agreement on standards. Just as one random example, being able to define what a lamp is and what fields a lamp should have,” Koster said. “If you’re trying to do that today, you might send that over the wire using JSON. JSON was actually originally SPECT, partly to solve exactly this problem in 2001.”

It took about 12 years to become a standard.

“The fact of the matter is that when we look at the technical challenges behind building a metaverse, they’re hard — harder than most people new to the field realize,” he said.

Lots of features need various kinds of standards, like the data format, a parser, the ability to be located at any remote location on the internet. And each of them requires an internet protocol ownerships solution as well.

“Each of these need to coordinate on multiple levels and share multiple standards in order for us to have any sort of prayer of truly building a coordinated metaverse,” Koster said. “This, of course, is why so much of building a metaverse pushes towards a single platform owner that can force these standards into existence. But we know that isn’t the dream we all ultimately want.”

A social problem

Koster said this is fundamentally a social problem.

“And if I if I had one big takeaway for everyone today, it would be don’t be seduced by the idea that technology can solve social problems and governance problems that humanity has been working on, in some cases for a couple of thousand years,” he said.

He said big social networks have spelled out some of the problem.

“Picture to yourself if you can, a metaverse with New York City or Tokyo or London. You can walk around and see absolutely everything annotated,” he said. “You can play a fantasy RPG running through the streets of a neighborhood where you can just log in and see the profile data on individuals and so on. That world operator has better data on you than the government does. Do we trust a tech company to have that kind of power?”

He added, “Are they going to replace the police? What are the ethical boundaries of having that sort of insight into society? And what rights do users have? When it comes to that? We all already know how hard it is to reach customer support at Facebook. How hard it is to persuade Twitter that maybe they ban someone by mistake, right?”

The recourse for citizens becomes harder and harder.

“The key seminal avatar rights document is something I wrote back in 2000. And you can find it in a dozen law textbooks. And to date, less worlds than there are fingers on my hand, have ever been willing to sign up to giving players actual rights in their virtual worlds,” he said. “That doesn’t even touch on the questions of what about copyright and trademark law. Because much of current IP law is outright incompatible with the way a metaverse might work.”

He said the major first conference that he attended on whether or not the metaverse might imply the end of the nation state was back in 2004.

“These are difficult problems. These are high level challenges. These are the kinds of questions that we as builders of alternate worlds, and people who are essentially translating the real world into something digital — these are the kinds of questions that it is our responsibility to grapple with,” he said.

Blindly setting off to go create something in hopes that it will just be better than the web is not responsible on our part, eh said.

“I would urge everyone here because I do believe everyone is idealistic. Everyone has high level dreams about what this can be,” he said. “I urge all of you who are listening to this, please go back, look at the history, learn from it. Find the ways to get around these key problems.”

Koster said he does believe we have ways of getting around those problems if we all work together “in order to take a step into this future that we all see barreling towards us at an incredibly high rate.”

It’s going to be hard.

“But I also believe that the potential for what we can do to improve human life is also incredibly high,” Koster said in closing. “And you know, like they say, everything worth doing is going to be challenging. With that said, welcome to the metaverse.”