Let’s get one thing out of the way first. Ownership of anything digital is illusory, and always will be.

Then again, it’s illusory in the real world, too. Ownership is a convention, not physical reality. This is why we have sayings like “Possession is nine-tenths of the law,” which basically means “you can claim you own something all you want, but if you don’t physically have the object, it’s pretty hard to enforce.”

In digital settings, of course, you never physically have anything. At best, you have a physical container of data.

Data is different

The characteristics of data are quite different from physical objects:

- It does not exist without a physical container of some sort, whether that be a piece of paper, a book, a CD, a hard drive, or cloud storage.

- It is perfectly replicable. By definition it can be duplicated infinitely.

- If I send you data over the wire – even if it’s encrypted! – I am basically handing you a full copy of it, which you could save off (controversies over this long predate the more recent “right-click save as” debates with NFTs). After all, to show it to you, we have to decrypt it on your machine, which means you have a copy of it in the clear.

Once upon a time, Stewart Brand said “information wants to be free.” That wasn’t just a philosophical statement. It was a literal description of digital data, which is effectively an infinite resource.

The history of computing is full of examples of trying to stuff this genie back in the bottle. It’s why we have software licenses, EULAs, subscriptions, dongles, DRM, and the DMCA. Oh, and everything about crypto. They are all about turning an infinite resource back into something scarce, recreating a non-digital world.

Lest we forget, the other half of Brand’s formulation was “Information also wants to be expensive, because it’s so valuable. The right information in the right place just changes your life.”

Economists have terms for these differences. To oversimplify, goods that only one person can have are called “rivalrous goods”, and goods that many people can have at the same time are“non-rival.” There’s also the notion of “Veblen goods” which are items that have increased value just because they signal status. Think of a really fashionable shoe – they aren’t any more useful than any other shoe, but they are more “valuable” because they are high-end, scarce, and fancy. You get the fancy shoe because it shows off the fact that you can get one.

All digital content, like all information, is effectively a non-rival good. But most ideas about “decentralized object ownership” or about “virtual items” in general are trying to turn them back into rival goods or even (in the case of NFTs) Veblen goods.

(Those who are more politically inclined among you may choose to veer off tangent here, and ponder the ironies in humanity taking the first truly infinite economic resource we have, something actually capable of creating an economy of abundance, and hemming it in with scarcity.)

Most people don’t even know what ownership is

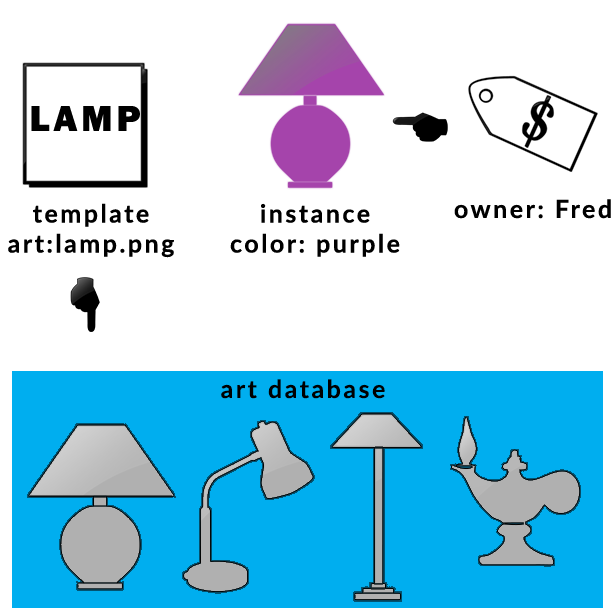

Over the last few articles, I’ve been sharing diagrams like this one:

These pictures have illustrated how the various conceptual pieces of a virtual object connect together. But all of these diagrams are missing a lot of connections that carry enormous weight – connections that aren’t all technical.

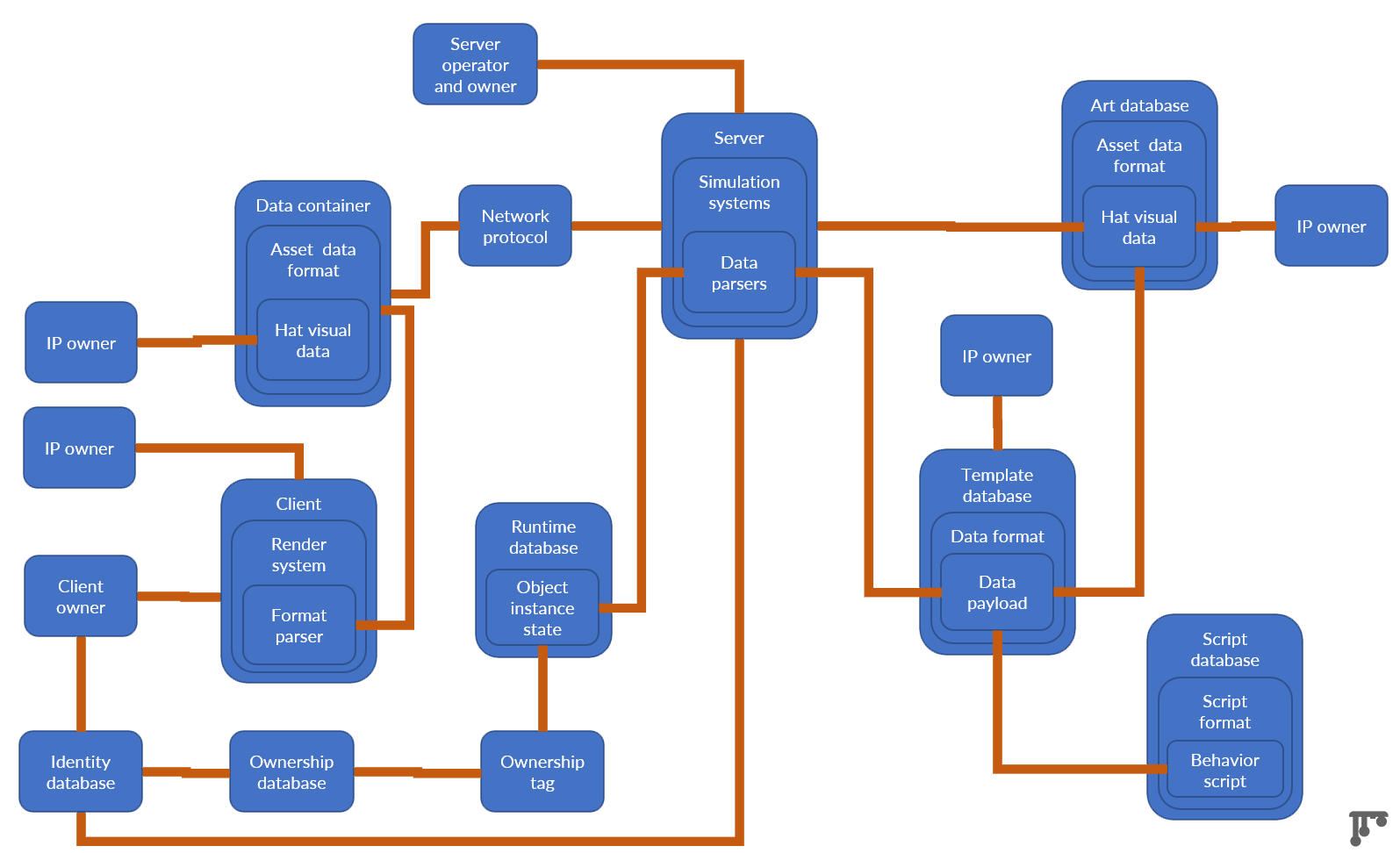

Here’s an actual map of a digital object set up for a cool distributed metaverse:

Still simplified, I’m afraid! Notice, for example, that it leaves out the question of who owns all the databases along the way.

In earlier articles, I emphasized that the data that made up a virtual sword existed in a format, and formats themselves then demand a system environment with a system that knows what to do with data in that format, and when you send it to the client, it needs another chunk of data, the art which is also in its own format and requires another parser to interpret it so it can be rendered, and so on.

All of this should sound familiar to you because it’s much the same as when you read a book. A story is data contained in a physical book. We shouldn’t forget that when you buy a book, you own the container and not the content.

Here’s another example. Let’s say you listen to a song. A song is data contained in a physical container. Here’s how that works:

- Someone wrote a song. This is something someone can own, thanks to intellectual property law, most specifically copyright.

- Someone then performed the song. A performance is actually the process of a human manually parsing the information data of a song, and turning it into a different set of data. This is also something someone can own.

- Someone recorded it. This recording captures the owned performance as data, and puts it in a container. (This container, the “master recording,” is what burned in the Universal fire of 2008, which destroyed the original master copies of countless classic albums). This is also something someone can own!

- The master is then rendered into different formats. These formats are each associated with a container. For a vinyl record, the format is literally a wiggly groove in plastic. For a digital recording, it’s a set of bits and bytes.

- Then the data has to get put into the matching container. Vinyl records. Cassette tapes. CDs. 8-track tapes. MP3s. Each of these is a container for the format for the recording of the performance of the song. And yes, someone can own this too!

- Then you buy one. You own the container. But each container is matched to a playback device. An MP3 is useless without an MP3 player which knows how to parse the data in the container and turn it back into the recording of the performance of the song.

- And once you have the vinyl of, I dunno, BTS or Taylor Swift’s latest hit, you tell yourself that you own the song. But you really don’t. A songwriter does, a music publisher does, and so on. You just own a container.

All of this is based on precedents such as “the right of first sale,” which is basically a legal rule saying that you can sell the container holding a song you bought to someone else; as well as the entire notion of copyright, which is all derived from the Statute of Anne in 1710, which basically invented the idea that the data and the container had different sorts of ownership.

What about virtual items?

Digital objects have the same subtlety as the above, complicated by these facts:

- They enable perfect copies at every stage of the chain. In fact, they make perfect copies at every stage of the chain. They even leave these copies scattered all over your hard drive!

- The server side can transfer the notion of ownership by just updating a column in a database. In a typical game, you never owned anything. You paid for the right to access a server which happened to keep some records linked to your character id.

To quote myself from an article from many years ago,

A digital item is made up of database entries. It’s bits and bytes living on a server. It may have been made by the same folks who operate the server, or it may not have. It may have been uploaded by someone who pays for the privilege of manipulating the data on the server, or it may have been uploaded by someone who gets access for free.

In some cases, these bits and bytes might be a unique arrangement of data, in which case it is probably copyrighted by someone. In some cases, it may actually be a record of activity instead, in which case and under some laws, it might be subject to privacy laws instead.

In no [legal] sense are any of these database entries “objects.”

As a result, digital stuff actually challenges the notion of ownership itself. You can’t have a doctrine of first sale for data, only for its container. Instead, we live in a world of software licenses, which has gradually evolved into subscribing to every bit of software that can get away with it.

Further, because “software eats everything,” we are seeing that license regime creep the other way and start making containers into something protected by copyright instead of being objects.

To quote myself again, “copyright controls who gets to make a buck.”

Copymess

The definition of copyright for a given medium has never been particularly pure – what is legal and what is not has entirely depended on who had better lobbyists at the time. It’s why the music industry managed to get a royalty on every blank cassette sold, but the software industry didn’t pull off the same trick with blank floppy discs. It’s why there’s a broader concept of “moral rights” in European copyright law than there is in the US legal system.

Where does this leave you with digital object ownership? The only real answer is “uncomfortable.” Because even when you explore cutting edge stuff like NFTs; delve into the controversies over right-click-save-as, pump-and-dumps, or energy consumption; whether you admire the tidy Veblen good markets around high end generative art NFTs or not – you still run headlong into the fact that all that tech is going to collide with copyright law in a messy way.

Put another way: if you get a cool branded digital object in MegaWorld, and you move it to NiftyWorld in the metaverse… some rightsholder may tell you “no, you can’t do that, because we don’t have a publishing agreement with NiftyWorld. MegaWorld has exclusive rights, and I don’t care that you own this.”

And there is always a rightsholder. The law creates that rightsholder by default the moment the work in question is created.

Laws are social constructs, of course. They can change and evolve. Our own relationship to songs and stories has changed tremendously as the technology of containers has evolved. Tech does not replace laws… but it does reshape them. Old hands at virtual worlds have known that viscerally ever since the first experiments in allowing players to govern themselves failed in spectacular fashion. (cw: rape).

In other words, ownership is actually just a tiny category in the larger issue of governance. It’s a huge category error to believe that tech can solve governance. But that hasn’t stopped idealistic technologists – myself included! – from trying.

But at that point, we’re done talking about “how virtual worlds work”… and instead, we’re talking about “how people work when in virtual worlds.” And that’s a whole family of topics for another day.

Check out the other articles in the series

How Virtual Worlds Work – Part 1

How Virtual Worlds Work – Part 2

How Virtual Worlds Work – Part 3

How Virtual Worlds Work – Part 4

How Virtual Worlds Work – Part 5